Stolen Name: How Software Erases Identity

Published:

Names are one of the first things a system asks for, and one of the easiest ways it reveals what culture it was built for. This post looks at how seemingly harmless assumptions in software can quietly erase identity, using Chinese names as the primary case study.

In my junior years as a software engineer designing APIs to relay user information for voice AI, my mentor, David, shared a classic post: Falsehoods Programmers Believe About Names. It was humorously eye-opening at the time. My favorite is the last one:

40. People have names.

We often model “name” as a tidy schema, then watch reality break it.

As someone who has built user-facing systems, I notice how the design of something as small as a name field encodes an entire worldview. Details such as whitespace, commas, and capitalization become cultural choices with real human consequences.

The Issue: When Given Names Have Spaces

Take my given name: Junru.

On my passport, my name is romanized as “Ren, Junru.” That works fine in most Western systems: two tokens, mapped cleanly to family and then given names. When a service greets me, I usually see “Hi Junru!” No drama.

In reality, my given name is formed by two characters, Jun and Ru, as is common for many Han Chinese names. Mainland documents romanize those two characters as one token (“Junru”). Outside mainland China, though, it is common to romanize with a space (“Jun Ru.”) or with a hyphen (“Jun-Ru”).

Here’s where the breakage starts. Many systems assume a first-space split and misinterpret the space as a boundary between first and middle names, illustrated in this simple Python snippet:

first_name = full_name.split(" ")[0]

last_name = full_name.split(" ")[-1]

Neat. Deterministic. And, for “Jun Ru Ren,” it yields first_name = "Jun" and last_name = "Ren", silently truncating half of the given name. As a result, one might be greeted as “Hi Jun!” instead of “Hi Jun Ru!” When others look up this name in a directory, they might see “Jun Ren”. A small bug becomes a small erasure.

This happens to friends who grew up in North America with given names romanized as two words. The downstream effects are social as much as technical: some eventually go by the truncated first token; others adopt an English name to avoid constant friction. Technology didn’t force the choice, but it nudged it.

Beyond Chinese Names: A Global Pattern

The point isn’t that Chinese names are uniquely tricky; it’s that a single schema can’t represent the world:

- Some Indonesians and Burmese people have mononyms: no family name at all.

- Icelandic names are primarily patronymic/matronymic, not stable family surnames.

- A favorite example: the Icelandic-Chinese jazz superstar Laufey. Her full name is Laufey Lín Bing Jónsdóttir where Jónsdóttir = Jón + s + dóttir, meaning “daughter of Jón.” Her Chinese name 林冰 (Lin, Bing) is proudly included, with Lin being her mother’s family name. Interestingly, her twin sister Júnía Lín Hua Jónsdóttir appears as “Júnía Lin” in production credits.

- Many Spanish-speaking cultures use two family names (paternal and maternal).

- In parts of India, name order and presence of a family name vary widely by region and language.

Yet many forms still require “First Name” and “Last Name,” full stop.

A helpful resource for developers trying to do better is the W3C write-up, Personal Names Around the World. The short version: accept variability, avoid premature parsing, and don’t assume structure from whitespace.

Appendix: How Chinese IDs Treat Names (Chinese Script)

When names are written in Chinese characters, the segmentation problem mostly disappears. Across most local ID systems, the full name appears as a single string of characters without explicit “first/last” fields.

| Sample | Remark |

|---|---|

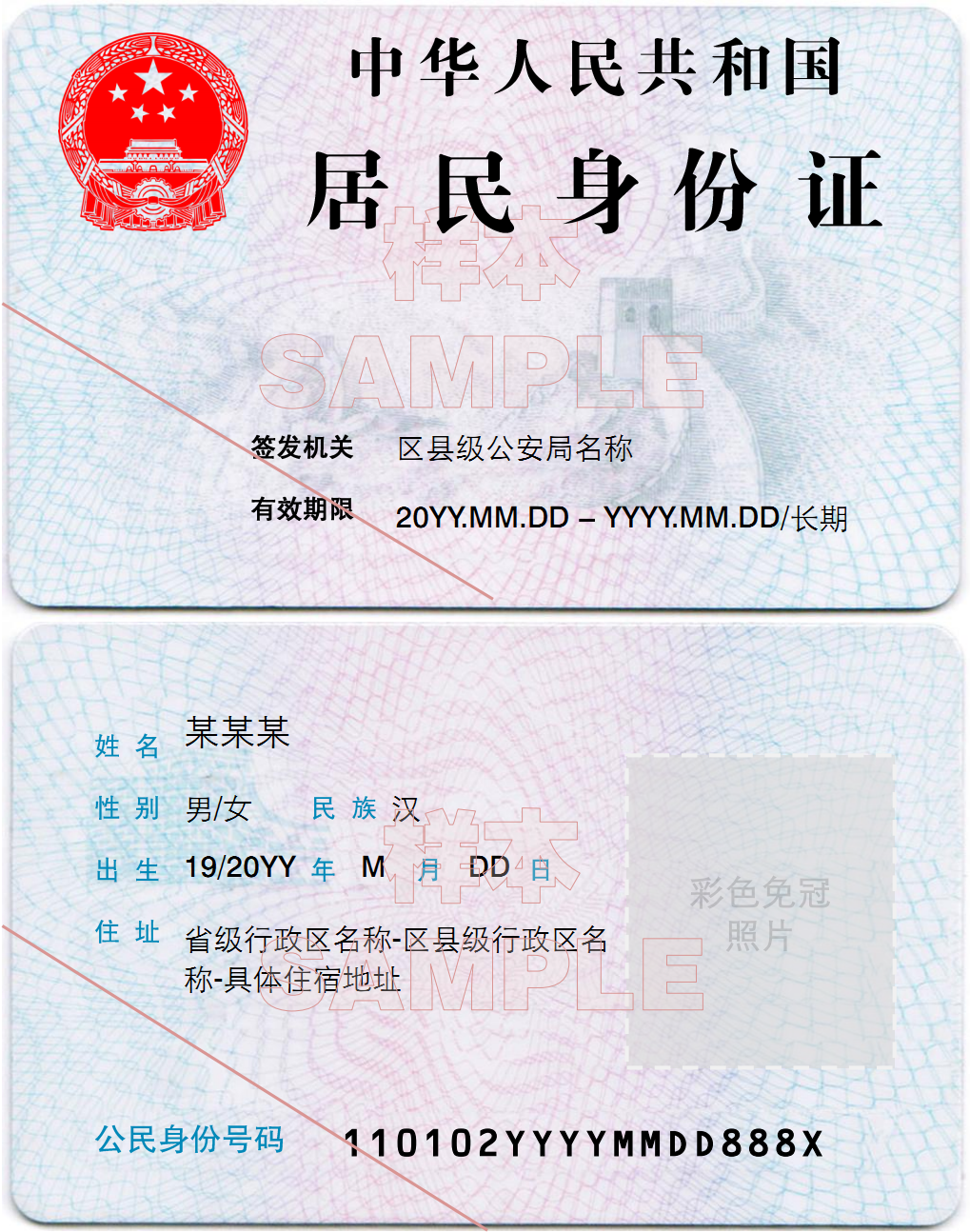

| Mainland China Resident ID Card shows one “full name” (姓名) field with characters together. In the sample photo, look for “某某某” as the placeholder of a full name. Some ethnic minority formats differ; see Additional Features |

| ID in Taiwan likewise shows one name field (姓名). Spacing between characters is typographic, not a given/family separator. |

| Hong Kong: the Chinese line shows characters together; the English line separates with a comma between family and given names. |

| Macau is a notable case where the card’s design explicitly separates family and given name fields. |

These examples (Macau aside) illustrate a key idea: in the native script, names are treated as a single unit; the friction arises during romanization and in systems that overfit to another schema.

Flip the Table

We’ve looked at what happens when Chinese names meet systems designed around Anglo‑American conventions. Now imagine the reverse: a non‑Chinese name forced into a Chinese schema with no space‑based segmentation, or an interface that insists on family‑name‑first without a clear family name to give. It could go both ways.

If you have stories, what worked, what broke, I’d love to learn from them.

Closing Thoughts

Whether in code or culture, the smallest design decisions shape how people see themselves. A name is not just data to be parsed; it’s a story, often written across languages and generations. When we build software, we are choosing which stories appear whole. Next time you see a field labeled “First Name”, pause and ask: whose first name?